JAN 19,2026

Read Time : 7 mins Approx

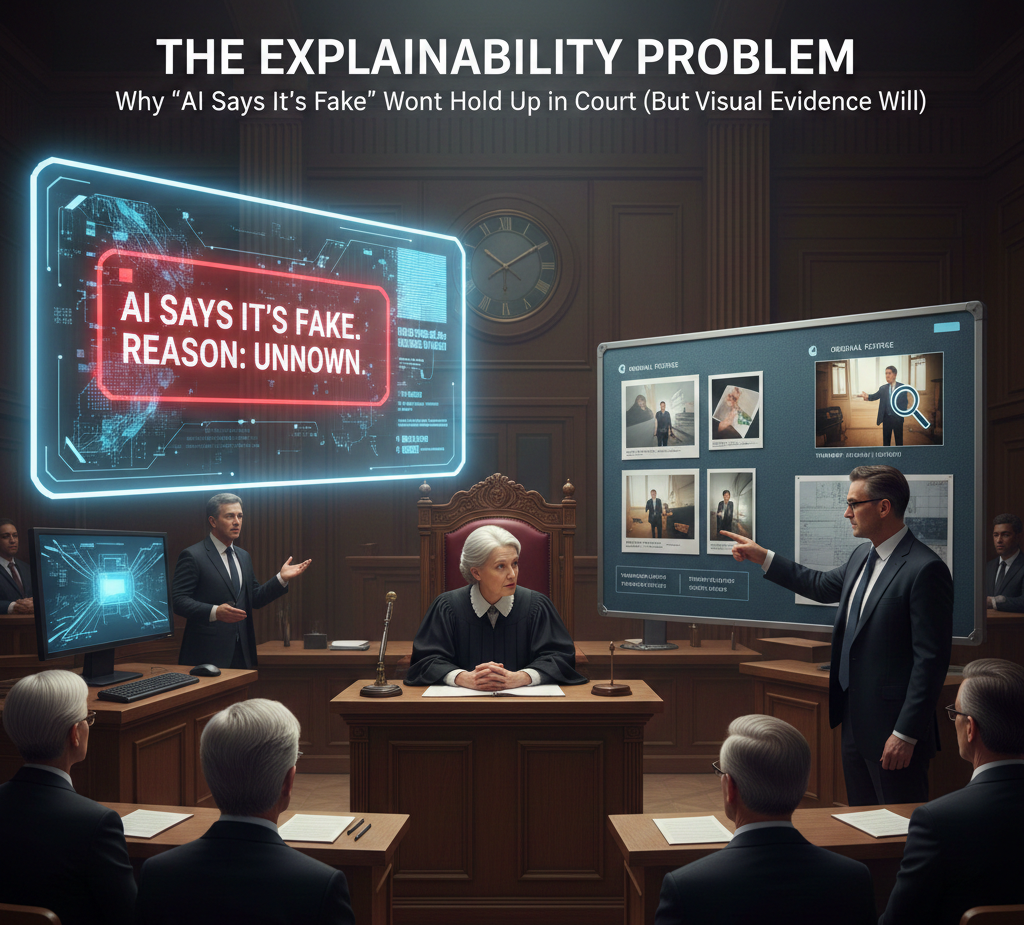

Last month, I was on a call with a defense attorney working on a fraud case. She'd been reviewing our deepfake detection reports for weeks, and then she asked me something that honestly stopped me in my tracks: "Your AI says this video is a deepfake. But can you actually show me why?

"It wasn't a technical question, at least not really. It was a legal one. And for most deepfake detection tools out there today (including some very well-funded ones), the honest answer is: no, they can't.

This conversation has been stuck in my head ever since, because it exposed something we in the AI world don't talk about enough: we're building tools that make confident proclamations about truth and falsehood, but when someone asks us to explain our reasoning in a way that actually matters (like, say, in a courtroom), we often have nothing to show.

Here's the thing about courts: they have this framework called the Daubert standard (named after a 1993 Supreme Court case, if you're curious). It's basically a set of rules that determines whether scientific evidence can be used in court. One of the big requirements? The methodology has to be explainable, and the reasoning has to be testable.

Now, imagine you're a forensic expert on the witness stand. The prosecutor asks you to explain why a video is fake. You pull up your deepfake detection tool, and it shows: "Confidence: 87% fake."

The defense attorney stands up: "Can you tell the jury which specific frames led to this conclusion?"

"Well, the neural network flagged it..."

"What exactly did it flag?"

"The model detected patterns consistent with manipulation..."

"Which patterns? Where in the video?"

Actually, "trust me, bro", turns out, is not a legal argument.

We've built AI systems that can detect deepfakes with impressive accuracy (and I'm genuinely excited about what's possible!), but we forgot to make them explain themselves in ways that legal systems can actually work with.

It's kind of like Sherlock Holmes solving a case but refuses to share their reasoning; impressive, sure, but not particularly useful when you need to convince a jury.

I've been talking to forensic experts and attorneys who deal with manipulated media cases, and they keep running into the same wall. Let me paint you some scenarios that can happen.

The Insurance Case: A company denies a $200,000 claim because their AI flags the damage photos as AI-generated. The claimant sues. In court, the expert witness presents a confidence score of 78%. The defense attorney asks what specifically triggered that score. The expert can't answer, not because they're incompetent, but because the tool doesn't provide that information.

The Criminal Defense: Someone's accused of impersonating another person in a video call to commit fraud. The prosecution has a detector that says "manipulation detected." The defense demands specifics. Where in the video? What artifacts? Without visual evidence of specific anomalies, the case weakens.

These aren't hypotheticals. They're happening right now, and accuracy isn't enough if you can't explain how you got there.

When we started building Authenta, we made a simple decision: every detection should come with visual, reproducible evidence. Not just a score. Actual evidence that a forensic expert can examine and that makes sense to a jury.

For Faceswap Deepfakes: Our system generates visual overlays highlighting specific problematic regions. Inconsistent lighting around the jawline, frequency artifacts near the eyes, texture mismatches where the fake face meets the real neck.

For AI-Generated Images: We provide attention maps showing which regions exhibit patterns inconsistent with how real cameras work. These are precise indicators of where the generative model left its fingerprints.

Look, I get it. If you're reading this, you're probably not planning to end up in court anytime soon (and I hope you never do!). But here's the thing: the legal requirement for explainability is really just a manifestation of a broader principle that applies to anyone using AI detection tools.

If you're in legal tech or forensics: You need detection evidence that will survive people asking hard questions about it. That's literally your job. Confidence scores are going to get you embarrassed in cross-examination.

If you're handling insurance claims: When you deny a claim based on AI-detected fraud, you're making a decision that affects someone's life and money. You need to be able to defend that decision with more than "the algorithm said so," both ethically and legally. The cost of losing these cases in settlements, in reputation, in regulatory scrutiny far exceeds any savings from cheaper detection tools.

If you're in HR or recruitment: In our world of remote hiring (which isn't going anywhere, by the way), you're going to encounter disputed video interviews. Maybe someone's interview gets flagged as a deepfake, and they claim it's a false positive that cost them a job. Can you show your work? Because if you can't, that's a lawsuit waiting to happen.

If you're in law enforcement: Building cases that lead to convictions requires evidence chains that hold up under intense scrutiny. Your detection tools need to produce documentation that forensic experts can testify to under oath without looking foolish.

The common thread here? In any situation where stakes are high and decisions matter, "the AI said so" isn't going to cut it. We all kind of know this intuitively (it's why we don't trust black-box algorithms with high-stakes decisions in other domains), but somehow we've been giving deepfake detection a pass.

So how do we actually achieve this level of explainability? I'll try to keep this accessible, but forgive me if I geek out a bit this is genuinely fascinating stuff:

Spectral Analysis: We examine images and videos in the frequency domain (think of it as looking at the "sound" of an image rather than just the picture). Generative AI models leave consistent artifacts in these frequencies that are invisible to your eyes but mathematically measurable. And crucially, we can visualize these artifacts and show them to people.

Anomaly Detection: Instead of trying to learn what deepfakes look like (which becomes obsolete the moment a new tool launches), we learn what real media looks like and flag deviations. This is more generalizable (it works on deepfakes we've never seen before) and it's more explainable because we can point to specific statistical anomalies.

Multi-Modal Verification: We don't rely on a single signal. Our system examines facial consistency, lighting coherence, temporal stability in videos, texture patterns multiple aspects simultaneously. When we flag something, we document which signals triggered the detection and why. It's redundancy that builds confidence.

Deterministic Output: This is crucial for legal contexts the same input always produces the same output and the same visual evidence. If you submit a video for analysis today and again next month, you'll get identical results. Many neural networks can't promise this because of their stochastic nature, but reproducibility is non-negotiable for court admissibility.

Beyond the detection itself, we've built in what I think of as the "boring but essential" documentation layer: time-stamped analysis reports, version tracking of detection models, chain of custody documentation, exportable evidence packages that can be shared with opposing experts. These aren't sexy features that make for good demos, but they're what separates a research project from a tool that works in the real world.

As deepfakes become more common in legal proceedings, we're seeing regulatory wheels start turning. The EU's AI Act includes provisions for high-risk AI systems, which would include detection tools used in legal contexts. Several US states are drafting legislation around digital evidence authentication.

Organizations that wait for these regulations before addressing explainability will find themselves scrambling to retrofit their systems. It's always harder to add explainability after the fact; it needs to be baked into the architecture from the beginning.

I've been thinking a lot about why explainability matters beyond just the legal requirements. It's easy to get caught up in accuracy metrics (we all do it; I certainly do), but accuracy without explainability is kind of like having a really smart friend who gives great advice but refuses to explain their reasoning. How much would you actually trust that friend with important decisions?

The explosion of deepfakes is forcing us to rebuild trust in digital media from the ground up, and that rebuilding process requires transparency. When I tell someone their video is a deepfake, I owe them an explanation. When a court relies on my tool to make decisions about someone's freedom or financial future, I owe them evidence. When a company uses our platform to make hiring or claims decisions, they owe their stakeholders defensibility.

"The AI said so" isn't just legally insufficient it's ethically insufficient. We can do better. We have to do better.

The next time someone asks whether your deepfake detection tool can hold up in court, the answer shouldn't be about accuracy percentages or impressive sounding neural network architectures. It should be about evidence.

Can your tool show exactly why it reached its conclusion? Can it produce visual, reproducible proof? Can a forensic expert examine and validate the reasoning? Can it survive cross-examination by a competent attorney who took a weekend course on AI?

Because in the legal system and honestly, in any system where we're making decisions that affect people's lives "the AI said so" isn't an argument.

But visual, explainable, reproducible evidence? That's something we can work with.